10,000 years of food culture

From economical use to carefree waste

by Heini Hofmann

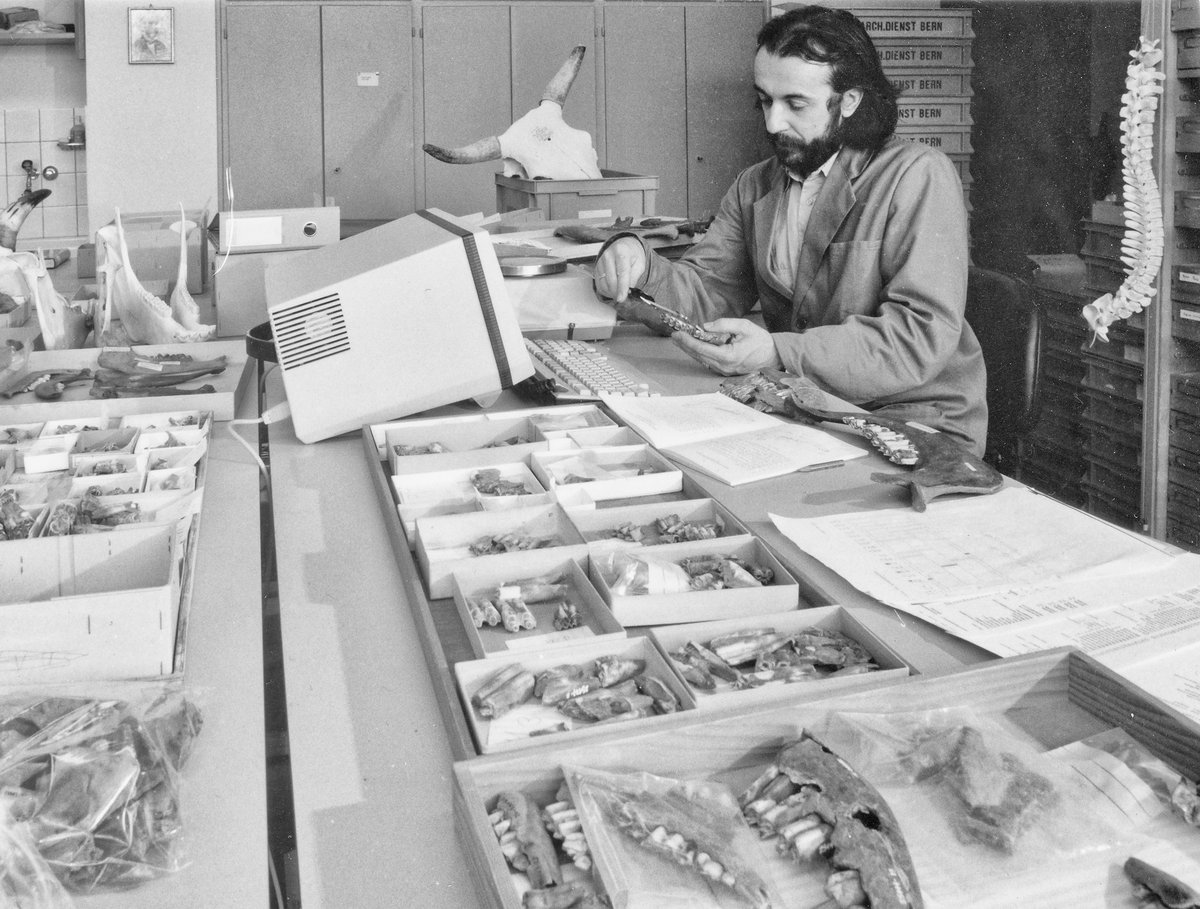

Thanks to archaeozoology, the study of slaughter and kitchen waste, food culture can be traced back up to 10,000 years. Conclusion: over the course of time, man was increasingly less wild about game; instead, his table manners became more and more extravagant.

Such a relaxed approach to animal resources runs parallel to increasing meat consumption based on farmed animals instead of wild animals. The menu of our ancestors since prehistoric times is now reconstructed with the most modern methods of archaeozoology, using food waste, especially bones. This allows conclusions to be drawn about eating habits, hunting selection among wild animals, age of the farm animals on slaughter and cutting methods.

Examples from four epochs

In the course of evolution, man has developed into a food specialist, a mixed food eater with good opportunities to use protein-rich food of animal origin. The dentition and digestive system speak for this. In the beginning, game was one of the possibilities to enrich food energetically.

Over four epochs it can be traced how game lost its importance with the rise of livestock farming and increasing civilisation. While in the Mesolithic period meat consumption was exclusively covered by game and fish, in the Neolithic period this was just a good third of the consumption. In the Middle Ages, the proportion of game in total meat consumption fell to a modest five per cent, and today it is still just over one per cent.

Hunters of the Mesolithic Age

When the last ice age came to an end, a shrubby tundra spread over the territory of present-day Switzerland, slowly giving way to emerging forest growth. That was 8000 to 5000 years before our time. The people of the Mesolithic period roamed the region, living in caves and tents, as nomadic hunters through a region rich in forests and game. They made tools and weapons from flint.

The meat content of their food consisted of one hundred per cent venison. One such settlement site of the Mesolithic was the Birsmatten Base Grotto near Nenzlingen, in a rock cave in the Birstal. The “waste zoologists” found over 15,000 bones and splinters during the excavations, of which just under 2,000 could be identified.

No waste

Although small bones and fishbones are badly preserved, it could be concluded that the Birsmatten inhabitants based their hunting grounds on beavers, otters, fish and frogs from the river Birs, deer and wild boar from the valley floor and chamois from the Jura heights. When they ate their haunch with fruits and nuts, they were probably not thinking of nouvelle cuisine …

But there was one thing they were far superior to us, namely their thriftiness, their economical use of the laboriously captured resources. Prey animals were exploited to the last detail, even the smallest bones were opened to make use of the fat-rich marrow. What would the Mesolithic people think if they saw how today’s consumer society treats offal, udders, pig’s feet and sometimes even calves’ heads as slaughterhouse waste, or how it disposes of male day-old chicken and old soup chickens on a massive scale?

The archaeozoologists came to the same conclusion at all the settlement sites in the Birs Valley: wild boar and deer dominated the menu, ahead of beavers, roe deer, chamois and badgers. Other Mesolithic settlements in the Central Plateau differed from the Jurassic ones in the wild boar hit parade: more elk, but no chamois.

Huntsman-farmers of the Neolithic period

Around 5000 B.C. the first “change-oriented” people lived; they turned everything upside down. Instead of chasing the animals, they tamed and bred them, and cultivated plants. Thus they became sedentary cattle breeders and farmers who changed the landscape by clearing the land. More often they built their settlements near lakes, which made water transport and fishing possible.

Their household goods also became more comfortable: finely crafted tools made of materials such as flint, bone and deer antlers, complemented by clay vessels. The Twann settlement area on Lake Biel is known from the Neolithic period, around 5000 to 2000 years BC. More than 200,000 bones have been excavated here, which, together with found plant remains, have resulted in archaeological food lists.

More beef, less venison

The species could be determined from around 14,000 bone finds. Domestic animals now dominated on the menu with 65 per cent compared to game. The largest supplier of meat, milk and fertilizer was cattle, ahead of sheep and goats. Nevertheless, hunting still played a prominent role with 35 per cent game, especially the red deer. But also wild boar and deer supplied animal protein. In addition, the Neolithic people consumed cultivated and collected wild plants.

Even back then, there was something like food landscapes with considerable variations on the menu: for example, the Neolithic settlers at Lake Burgäschi (not far from today’s Museum of Game and Hunting at Landshut Castle, Utzenstorf) lived almost exclusively on wild animals, while the meat ration of their contemporaries from the lower Lake Zurich was based on domestic animals to the tune of eighty per cent. Goldcoast even then?

Farm hunters of the Middle Ages

At the time of the foundation of the Swiss Confederation, cattle breeding dominated, and yet the hunter’s lust was by no means extinguished, so that it is no coincidence that Willhelm Tell is characterised as a chamois hunter when his son Walther sings the song “Mit dem Pfeil, dem Bogen” and hunter Werni asserts “Das wissen wir, die wir die Gemsen jagen”.

“Just stay away from there today. You’d better go hunting”, Hedwig advises her Tell, and he himself growls into his beard, while he lurks for Gessler behind the elder bush: “The projectile was only aimed at the forest animals, my thoughts were pure of murder”. However, one thing is certain: twenty kilometres east of Bürglen, beeline, where Tell is said to have lived at 1650 metres above sea level, above the Braunwald in Glarus, there was the “Alp desert” of Bergeten, of which more details are known.

Primary cattle, marginal game

In the 13th/14th century this settlement was inhabited in the summer half of each year. The Alpine pastoral population left little waste: a few horseshoes and only 500 bones, of which less than 300 could be identified. At least it could be determined: Meat suppliers on Bergeten were the milkable horn-carriers, primarily cattle, but also goats and sheep.

Finds of bones and hunting weapons indicated that there was also hunting, namely bear, chamois, marmot and hare. Which also means that Schiller did thoroughly research for his “Tell”. But that the hunt was already on the downward spiral is also proven by other excavations from the same period in the Alps and the Central Plateau. The proportion of venison in the meat consumed was only five per cent.

Consumers of the present

Centuries after our time, archaeozoology may well have an even more difficult time; although our consumer and throwaway society leaves behind an infinite amount of food waste (around five million tons), not so much in the form of bones as canned food.

Game plays only a marginal role on the plate of modern society, just over one per cent of all meat consumed. Appropriately, the meat statistics are as follows, more than 440,000 tons of carcass weight of farm animals and a good 70,000 tons of fish, molluscs and crustaceans are offset by around 5,000 tons of game (furred game and feathered game).

One third of a sod

Of the approximately 5000 tons of total game, about 2800 tons are imported (mostly from farmed animals) and only about 2200 tons are taken from the native wildlife. The Helvetic fenced game farms (fallow deer) contribute about 60 tons.

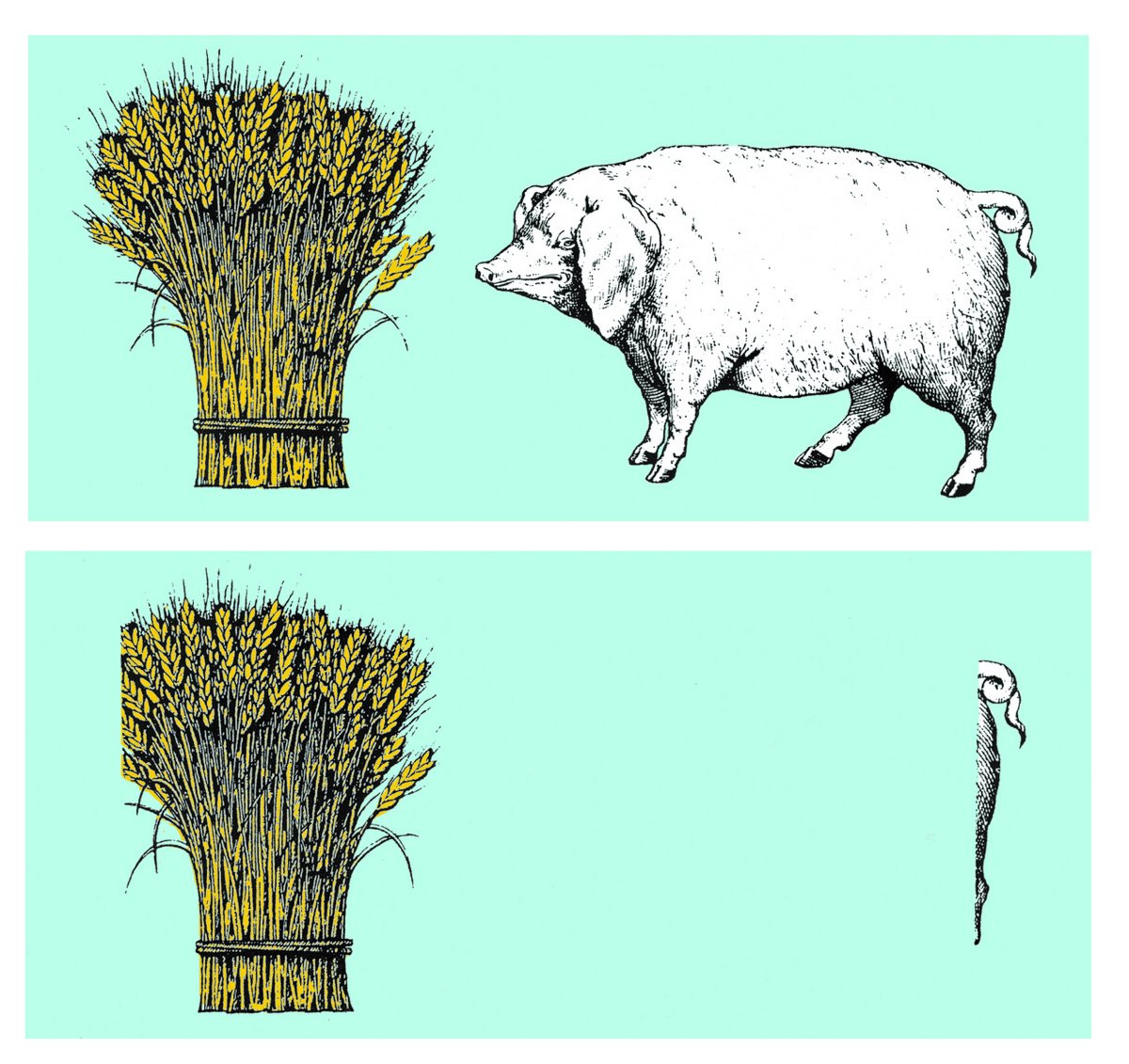

The current annual meat consumption (boneless) of an average Swiss person is a good 50 kilogrammes, almost twice as much as at the end of the last world war. However, only just under 500 grammes, less than one per cent of this comes from wild animals, and thereof in turn only just under 200 grammes from local hunting. In contrast, the average Swiss devours one third of a sow per year, except for the meat of other farm animals. •

(Picture NMB)

(Picture NMB)

(Picture NMB)

Pets versus wild animals

hh. After the last ice age, venison still played a central role in the diet (especially deer, wild boar, roe deer and bear), but in the course of civilization more and more domestic animals became meat suppliers (cattle, pigs, sheep and goats). Today, grazing plays only a marginal role in nutritional terms. The agriculturally produced meat has replaced the meat grown in the wild. At the same time, consumer habits have changed, from thrifty use to carefree wastage. If we used the carcasses of our farm animals as thoroughly as the Stone Age people used their wild animal prey (then almost one hundred per cent, today only 50 per cent), we would need much fewer slaughter animals, with positive ecological and economic consequences. Perhaps our wasteful consumption of farm animals would have to return to the close-to-nature customs of hunting!