Syrien - quo vadis?

“Even during the war we did not face problems like this”

by Karin Leukefeld, Damascus

The explosion in the port of Beirut (on 4 August 2020) also shook Syria. Lebanon and Syria have close social, economic and political ties. During the war and siege, for a besieged Syria, Beirut has been the gateway to the world, through which people have been able to travel and come back, through which trade has not stopped. For Lebanon, Syria is a source of fruit, vegetables and food which are no longer cultivated in sufficient quantities in Lebanon itself. The corona pandemic restrictions imposed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) led to the closing of all but a few of the joint border crossing points. This means the end for Syrian refugees and workers in Lebanon. Shops along the road to the Lebanese-Syrian border are deserted.

“Even during the war we did not face problems like this.” If you ask the people in Damascus, Homs, Hama or Aleppo about how they are doing, the answer is always the same, as if they had agreed in advance. Work, health, the supply of food, electricity or petrol – everything was better during the war than it is now in 2020. At least it seemed to be more bearable, because people expected the war to be over soon, and then the country could be rebuilt. Nobody thought it would be easy, but such problems were not expected.

Whether they are merchants, traders or farmers, children or grandparents, young or old, each of them complains about the lack of electricity and petrol, the loss in value of the Syrian pound and the enormous inflation. Most of them have cut cheese, eggs, milk and yoghurt out of their daily diet. A kilo of lamb costs half a month’s wages, and even a chicken is not affordable. “A chicken costs 10,000 lira,” calculates Hanan, who works in a family hotel in Damascus. Like all Syrians, he uses the old name of the Syrian currency “Lira”, officially it is a Lebanese pound. In the spring, Hanan’s monthly wage was raised from 50,000 to 70,000 lira, but it’s still not enough for the family of five and Hanan’s father, who lives with him. In spring, the wage was worth the equivalent of nearly 60 euros, but today it is only 30 euros. “10,000 lira for a chicken,” Hanan sighs and gestures with his hands. “How could I buy a chicken when I have 70 000 lira a month? We have not had any meat for months!”

“We’re getting strangled,” Delal H., a retired gynaecologist in Damascus, agrees. Considering the acute shortage of specialists in Syria, the dedicated woman still carries on working in the hospital every day spreading optimism for professional reasons in itself. She is fond of showing the photos of “her” children she helped to give birth. On this day, however, she literally seems “beside herself”. “We have US military bases in the country, Israel bombs us when and where it pleases! Sanctions are preventing reconstruction, the Caesar law is threatening anyone who wants to help us. They are stealing our oil, and now – with Corona – things are getting worse. What do they want from us? Where is this going to end!”

There was no hunger

Life in Syria is getting hard. While international aid convoys carrying the UN flag are travelling from Turkey to Idlib via the Syrian-Turkish border crossing at Bab al-Hawa to supply the people there with medication, food, powdered milk, protective equipment against the new virus and much more, the Syrians in the rest of the country are somehow trying to keep their composure.

There was no hunger. Until 2010, Syria had not only supplied its own population and neighbouring countries with its agricultural products, but it had also been able to export food, says agricultural engineer Haitham Haidar during a detailed discussion in Damascus. Haidar is a friendly, calm man who is responsible for planning and international cooperation in the Syrian Ministry of Agriculture.

In 2020, only about four million hectares of the six million hectares of available agricultural land in Syria, could be cultivated. The reasons are many and varied, says the engineer: “Experienced workers are lacking, sanctions prevent the import of fertiliser, machinery and spare parts. 60 per cent of our agricultural facilities such as silos and storage facilities, factories for food production and numerous agricultural research facilities have been destroyed in the war.” Moreover, Syria has lost about half of its livestock. The worldwide appreciated Awassi sheep are a great loss. “In 2010 we had 15 million of them, this year only 7 million were counted.” Bedouins, who recognise neither state nor borders, might have sold the animals in Jordan, Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

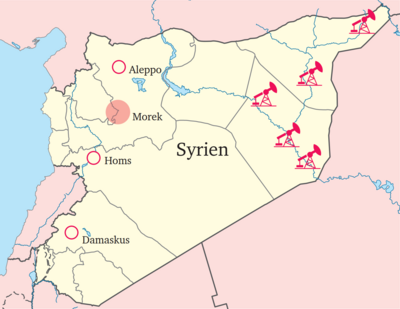

Nevertheless, considering the difficult situation, the 2020 harvest was good, the engineer emphasises. However, the shortage of petrol and oil makes transport from the producer to the consumer more difficult and expensive, and also increases the selling price. “Our oil resources in the north-east of the country are being occupied by the Americans, and the import of oil – from Iran, for example – is being hampered by the sanctions”. Harvests north of the Euphrates and in Idlib are illegally sold to Turkey and northern Iraq, Haidar said. “The destruction of our agriculture is a deliberate act”.

A greeting from Morek

You can see this while driving through the provinces Hama and Idlib to Aleppo. Besides Al-Hasakah in the north-east, Hauran in the south and Al-Ghab in the west, Idlib is one of the most important agricultural centres of the country. Khan Shaykhun, Ma’arrat al-Nu’man, Saraqib are places whose names have been heard in recent years in connection with war. Indeed, trade was flourishing in this area until 2010.

Fistik Halabi, the famous pistachios, are grown here, olive trees produce the best olive oil and the marble from the area is an export hit. Now the towns have been destroyed, villages to the right and left of the motorway have been abandoned, there are withered olive and pistachio trees and burnt oleander bushes on the central reservation of the motorway. A Turkish “observation post” has been established on the site of a grain silo, destroyed houses, workshops and factory buildings are lining the road.

Morek is known as the centre of the Fistik Halabi, the Syrian pistachios. The village is located about 30 km north of Hama and was a frontline to fighting units armed by jihadists in Idlib during the war. In the shadow of a Turkish military base surrounded by high walls – a so-called “observation post” – are the largest pistachio plantations. Wherever you stand, the plantations with their stocky, sturdy trees and dense foliage with umbellate fruits stretch to the horizon on fertile soil.

It is Friday morning when Mr Nasser from the Hama province media office accompanies us to the pistachio market in Morek. The place is still considered a military restricted area, so the Muchtar of Morek, the mayor, is waiting at the checkpoint. In the back seat of a military motorbike patrol, he drives ahead through the village, to which only a few families have returned. Morek is largely in ruins.

Farmer Ghazi Nassan al-Mohamed is the second generation of Fistik Halabi farmers to cultivate delicious pistachios. The harvest period lasts from July to November. Now, in September, the trees are harvested daily. Before the war, Mr Ghazi had 1,040,000 pistachio trees planted by his father, which were 40, 50 years old. “Old trees bring the best harvest, young trees can be harvested for the first time after 10 years”. Before the war, around 50,000 tons of Fistik Halabi were harvested in Morek, says the man wearing a galabiya, a shirt reaching down to the ground, which is traditional for Sunni Muslims. “This year we have only half of it at the most.” Trees were destroyed in the fighting, chopped down and sold because of the wood, the farmers were not there to protect and care for the trees.

When a van arrives honking loudly, the conversation is interrupted. There are baskets of fresh pistachios on the loading area. “Our harvest this year is important because the yield must be used to secure the new 2021 harvest,” Ghazi al-Mohamed explains moving his two hands into the baskets with the fruit. “In the past, the government helped us with fertilisers, with machines, with everything. Now we have to pay almost everything ourselves, the government is under pressure.” Quickly, a plastic bag is filled with fresh pistachios and handed over to the author. “Here you are, a greeting from Morek! May it taste good!” •