Agreements with other countries must benefit all parties

No to the free trade agreement with Indonesia

by Dr iur. Marianne Wüthrich

On 7 March 2021, we Swiss will vote on an “Economic Partnership Agreement” with Indonesia. The CEPA (Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement) is intended to newly regulate trade in goods between the EFTA states (Switzerland, Norway, Liechtenstein, Iceland) and Indonesia and replace previous agreements. It was signed by the contracting parties in December 2018, and the National Council and Council of States approved it on 20 December 2019.

The CEPA is a free trade agreement, which means that trade in goods is to be largely exempted from mutual customs duties. However, for the import of palm oil, which is controversial in Switzerland, the tariff is not to be abolished, but only reduced. In addition, a sustainability clause has been added to the text of the agreement – for the first time in a Swiss trade agreement – which Swiss importers must prove they are complying with.

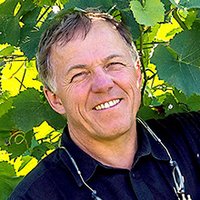

Sounds good – nevertheless, the farmers’ trade union Uniterre and the well-known Geneva organic winegrower Willy Cretegny, together with around 50 other environmental and farmers’ associations and political parties, submitted a referendum against the agreement on 22 June 2020 with more than 61,000 valid signatures. Why?

Main criticism: Sustainability only on paper

According to Article 8.10 of the Agreement, the Parties commit themselves to:

(a) effectively apply laws, policies and practices aiming at protecting primary forests, peatlands, and related ecosystems, halting deforestation, peat drainage and fire clearing in land preparation, reducing air and water pollution, and respecting rights of local and indigenous communities and workers;

(b) support the dissemination and use of sustainability standards, practices and guidelines for sustainably produced vegetable oils; […]

(e) ensure that vegetable oils and their derivatives traded between the Parties are produced in accordance with the sustainability objectives referred to in subparagraph (a).”

The control of compliance with these provisions is regulated in Article 8.13:

“The Parties shall periodically review, in the Joint Committee, progress achieved in pursuing the objectives set out in this Chapter […]. ”1

However, writing a report for the drawer every now and then is a weak instrument. The committee therefore denounces the lack of effective control: “The free trade agreement with Indonesia provides for the inclusion of sustainability provisions in environmental and trade standards. But the promise is hardly to be implemented, because effective control and sanction possibilities are missing.” Already today, there are almost 17 million hectares of palm oil crops in Indonesia – that is about 10 per cent of Indonesia’s surface area! – and more rainforest is constantly being cut down or burned. The Indonesian government is “not a reliable partner”, the committee continues: “The rule of law, sustainability and social standards are disregarded, small farmers, indigenous peoples and local communities are displaced. Inhumane working conditions, including child labour, and the use of highly toxic pesticides are widespread.” (Voting booklet, p. 50)

The movement “Stop Palm Oil!” adds why the sustainability commitment in the agreement would have little effect: “The RSPO guidelines (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) are insufficient and further fuel the destruction of peat bogs and species-rich rainforests. [...] And above all: the palm oil industry is to control itself, because compliance is controlled by the private organisation RSPO, which is dominated by palm oil producers.”2

Swiss food multinationals involved in the destruction of tropical forests

In its statement of 2 March 2020, Uniterre also points out that major Swiss corporations are at least aware of the overexploitation of nature: “Leading corporations such as Unilever, Mondelez, Nestlé and Procter & Gamble (P&G), as well as palm oil traders such as Wilmar, buy palm oil from producers linked to numerous fires in Indonesia, as an investigation by Greenpeace International in November 2019 shows.”3 The Nestlé Group does state in detail on its homepage that the company is making great efforts to only source palm oil from responsible and certified deforestation-free production.4 According to SECO, however, the above-mentioned and many other large Swiss companies have branches in Indonesia,5 which means that their managers are on the spot and can hardly overlook the forest fires.

However, the profits of Nestlé and other multinationals are hardly affected – neither with nor without a free trade agreement; they probably import little palm oil into Switzerland because their processing plants are located all over the world.

No harm for rapeseed farmers? Strange naive fallacy of the Federal Council

According to the Federal Council, “no negative effects [...] are to be expected on local rapeseed and sunflower oil production”. Because: “The tariffs will not be lifted, but only reduced, and this by around 20 to 40 per cent. These tariff rebates are granted for a maximum of 12,500 tonnes per year”. (Voting booklet, p. 47) This euphemistic formulation misses the reality in two respects:

- Enormously high maximum quantity: So far, Switzerland has imported only very minimal quantities of palm oil from Indonesia, namely an average of 2.5 % of a total of around 32,000 tonnes over the last eight years, and only around 0.1 % in 2019 (Voting booklet, p. 48). That is 35 tonnes – very little indeed. But with the free trade agreement, Swiss importers would be allowed to import up to 12,500 tonnes with the lower tariffs. From 35 to 12,500 tonnes – a real leap upwards! This would allow the Swiss agro-industry to obtain up to 40 % of the total palm oil imported today from Indonesia at more favourable prices. And the total imports are not supposed to increase? This forecast is confirmed by the fact that Switzerland’s palm oil imports from Indonesia have fallen sharply since 2013 (from Malaysia somewhat less), while those from Myanmar or the Solomon Islands have risen, “thanks in particular to the duty-free access granted by Switzerland as part of its development cooperation policy”.6 Well, if it’s part of Switzerland’s development aid, then it’s something else – provided that the proceeds really end up in the pockets of the small farmers of these states …

- Large price difference between Swiss oils and Indonesian palm oil to be feared: Let’s leave the floor to Uniterre: “The 12,500 tonnes of palm oil quotas are in direct and unfair competition with local oilseed production. A price comparison: Fr. 2.64/kg for rapeseed oil after processing, sunflower oil Fr. 2.59/kg face [today for palm oil] Fr. 2.51/kg (incl. customs duties). A 35 % reduction in customs duty, as stipulated in the free trade agreement with Indonesia, means a 40 centimes reduction in price. Rudi Berli, vegetable farmer and spokesman of the referendum committee, criticises: ‘The reduced tariff on palm oil imports increases the demand even more. Here, the aim of procuring agricultural raw materials as unhindered as possible and at the cheapest price is being implemented. With fatal consequences for people and the environment – solely for the benefit of the agro-industry’.”7

Swiss Farmers’ Union: Yes to the agreement – but not out of conviction

Quite strange is the reason given by the board of the Swiss Farmers’ Union SBV why it decided (practically unanimously) to vote in favour of the free trade agreement with Indonesia: The SBV had demanded a sustainability clause and a protection mechanism for the local oilseed production from the Parliament. “Both had been included in the agreement thanks to manifold political pressure, so the SBV could hardly say no now”. (Schweizer Bauer/Swiss farmer, 16 January 2021). Accoordingly, the parliament of the SBV, the Chamber of Agricurdingly, lture, voted yes by a majority in a (pandemic-related) written ballot, without the usual previous discussion.8

For the voter, it is certainly of interest how this yes vote came about – “Päckli politics” (packet policy) is what we call it in Switzerland.

The Swiss export industry does not only consist of large corporations …

The referendum committee must be contradicted on one point: It is true that in international trade, and especially in the palm oil business, many large corporations are making huge profits, but Swiss export companies also include numerous small and medium-sized enterprises (in total, more than 99 per cent of Swiss enterprises are small and medium-sized). The Swiss export industry is an important mainstay for the small landlocked country of Switzerland, which is dependent on imports of almost all raw materials. Just as a well-positioned agricultural sector is indispensable for the security of supply, the export businesses in trade and industry also need our support – at least the smaller ones. The big ones already look after their own interests.

In this sense, the President of the Swiss Confederation of Commerce (sgv), National Councillor Fabio Regazzi (political party The Centre – formerly CVP-Ticino) points out that many small and medium-sized enterprises would also benefit from the advantages of easier market access in Indonesia: “Almost a quarter of the Swiss exports to Indonesia would be due to mechanical parts. These are industries in which the smaller and medium-sized enterprises are disproportionately active. For him, as President of the Swiss Confederation of Commerce (sgv), it is therefore hardly surprising that the Chamber of Commerce, the parliament of the sgv, has unanimously supported this agreement.”9

This position of the trade association is understandable. Nevertheless, the customs duties for export companies that would be eliminated with the agreement would not be as enormous as one might think if one listens to the exponents of the trade associations.

… but today’s tariffs are not that high

The business association economie-suisse is campaigning for the abolition of the “relatively high” tariffs: “This free trade agreement gives Swiss export companies and SMEs an important competitive advantage over competitors from other countries, such as the EU. For example, thanks to the agreement, 98 per cent of the existing tariffs for Swiss exporters in Indonesia will be completely eliminated in the medium term. These are currently relatively high and average eight per cent for industrial goods. Swiss companies can thus save more than 25 million Swiss francs per year in the future.”10

(Parenthetical note: Here, Jan Atteslander, head of foreign trade at economiesuisse, is suddenly pleased that Switzerland is not completely in the EU’s internal market after all – perhaps the framework agreement with Brussels, when it becomes concrete, will not be so great for our economy after all? For example, with closer integration, Switzerland could no longer freely decide on trade agreements with other states.)

According to economiesuisse figures, the “relatively high” tariffs applied so far turn out to be rather moderate,11 namely around 5 % for SME products in the machinery sector and only 4–5 % for chemical and pharmaceutical products. A relatively low 5–10 % is also added to watches. For clothes and shoes, however, Indonesian import duties are quite high – and rightly so, because in this sector the local companies produce themselves and want to sell and export their own products. Only well-heeled Indonesians can buy Swiss cookies and chocolate, so the duties can be a little higher (15–20 %), and we can’t blame the government in coffee country Indonesia for adding 11 % to coffee from Switzerland – by the way, Nespresso capsules are expensive in their original form in Switzerland, too.

Swiss companies have been able to absorb these moderate tariffs (a total of 25 million Swiss francs per year, including large corporations) until now, and they will continue to be able to do so in the future. Switzerland has always been a cosmopolitan business centre, and our entrepreneurs are used to having to cope with competition from cheaper products from abroad. That’s why most are extremely flexible and innovative and make up for higher prices with top quality.

Trade agreements must ensure the protection of self-sufficiency

Trade agreements with other countries are not bad per se. But as Willy Cretegny – who initiated the referendum – says, they should be win-win agreements. That’s why they should not throw all protective provisions (tariffs and quotas) overboard: “There needs to be protectionism. For me, it’s a policy of openness because it’s based on respect for the choices of each people.” (see interview with Willy Cretegny in this newspaper).

To add: Good protective regulations are indispensable, especially for agriculture, if we want to rely on the highest possible level of self-sufficiency. In Switzerland, the people approved the anchoring of food security in the constitution on 24 September 2017, with 78.7 % and all the cantons voting in favour: According to FC Article 104a, the Confederation must create the conditions for “ensuring the supply of food to the population”.

Because the cost of living in Switzerland (also for farming families) is very high compared to the international market prices for agricultural products, we should not conclude free trade agreements that include agriculture. This is why the 1972 Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU was concluded with the exclusion of agricultural products and has worked perfectly well until today. But beware: If we were to approve the framework agreement with Brussels, we would also be giving the green light for the “modernisation” of the FTA, which means, among other things, that we would have to open the gates to the cheap mass-produced products of the agro-food industry in the EU.

FTA with Indonesia does nothing to support small farmers there

The Indonesian population (260 million inhabitants!) and the small farmers there are also not helped by the planned free trade agreement: They do not need palm oil monocultures, but – as the World Agricultural Report demands – local production to feed their families and the rest of the population. It cannot be that Indonesia has to import rice! Thus we read at Uniterre: “Before trade liberalisation, Indonesia exported rice, and today the country is forced to import around 2 million tons.” That is why the Indonesian Peasant Union (SPI) calls on the government there to “transform Indonesia’s agricultural model into agroecological agriculture and give priority to food sovereignty.”12 With an agreement that cuts down the rainforest in order to increase monocultures for the benefit of big corporate agribusiness, we are not contributing to this. •

1 Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement between the Republic of Indonesia and the EFTA States. Concluded in Jakarta on 16 December 2018. ((https://www.efta.int/sites/default/files/documents/ legal-texts/free-trade-relations/indonesia/efta-indonesia-main-agreement.pdf)

2 «Stop Palmöl! Nein zum Freihandelsabkommen mit Indonesien.» ” (Stop palm oil! No to the free trade agreement with Indonesia.)

3 Uniterre. Referendum against the free trade agreement with Indonesia. Statement of 2 March 2020. Greenpeace study: Burning down the House: How Unilever and other global brands continue to fuel Indonesia’s fires, https://www.greenpeace.org/malaysia/publication/2620/burning-down-the-house-how-unilever-and-other-global-brands-continue-to-fuel-indonesias-fires/

4 https://www.nestle.com/csv/raw-materials/palmoil

5 Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft SECO. «Indonesien» vom Juni 2019 (statistisches Update Juni 2020) (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO. “Indonesia” as of June 2019 (statistical update June 2020))

6 Agrarbericht 2020 des Bundesamts für Landwirtschaft BLW (Agriculture Report 2020 of the Federal Office for Agriculture FOAG.) . https://www.agrarbericht.ch/de/international/statistiken-und-modellierung/agrarstatistiken-einiger-handelspartner

7 Uniterre. Referendum gegen das Freihandelsabkommen mit Indonesien. (Referendum against the Free Trade Agreement with Indonesia) Statement of 2 March 2020)

8 «Bauernverband unterstützt Abkommen mit Indonesien.» (Farmers’ Union supports agreement with Indonesia). Media release of the Swiss Farmers’ Union of 25 January 2021

9 «Ein Pionierabkommen für nachhaltigen und fairen Handel. (A pioneering agreement for sustainable and fair trade). Media release of the sgv of 12 Janaury 2021

10 Atteslander, Jan; Ramò, Mario. «Ja zum Freihandelsabkommen Efta-Indonesien: Vorsprung für Schweizer Exportnation» (Yes, to the Efta-Indonesia free trade agreement: Head start for Swiss export nation). Economiesuisse of 3 December.2020, p. 8

11 Atteslander, Jan; Ramò, Mario. «Ja zum Freihandelsabkommen Efta-Indonesien: Vorsprung für Schweizer Exportnation» (Yes, to the Efta-Indonesia free trade agreement: Head start for Swiss export nation). Economiesuisse of 3 December.2020, p. 8

12 Uniterre. Referendum against the free trade agreement with Indonesia. Statement of 2 March 2020

“Free trade is harmful to our planet”

Interview with Willy Cretegny

The Swiss will vote on the trade agreement with Indonesia on 7 March 2021. The treaty is too lax on sustainability, says Willy Cretegny, the originator of the referendum. He questions the principle of free trade in general. For the organic winegrower from the canton of Geneva, it is all about the big picture: the principle of free trade must be questioned, he says in an interview.

swissinfo.ch: Mr Cretegny, what bothers you about the principle of free trade?

Willy Cretegny: It aims to reduce or abolish all tariff and non-tariff measures, although these are very important for fair trade and to avoid distortions of competition. Taxes equalise prices from one economy to another and have a strong impact on our consumption. Free trade gives us access to many goods at prices that have nothing to do with our purchasing power. So we consume more and more. The distortion of competition makes whole sectors disappear.

Let’s take Ikea as an example. The corporation produces a large part of its cheap furniture in Asia, imports it practically tax-free to Europe and Switzerland and sells it there at low prices. This destroys domestic suppliers. The workers are paid according to the collective agreement, but their wages require state support for housing and health insurance. Finally, the family that owns the company is one of the richest in Switzerland. By abolishing customs measures, free trade has become an instrument for tax exemption.

What do you propose instead?

I advocate a win-win agreement that benefits everyone. Basically, I want the importance of tariff and non-tariff measures to be recognised. There needs to be protectionism. For me, it is a policy of openness because it is based on respect for the choices of each people.

In contrast to this is the principle of free trade, as propagated by the World Trade Organization (WTO), for example. All it cares about is that trade and profit grow steadily. Today, we are levelling, standardising and developing a system that is extremely harmful to our planet. Switzerland should set a good example.

Of course, we cannot change our practices overnight, as we are already involved in many contracts. But we need to give our negotiators a different mandate so that such contracts take into account these social and environmental issues and aim to enforce local standards.

You think that the agreement is too lax with regard to sustainability. Why?

The treaty provides for arbitration in the event of a dispute, but the article on sustainability is excluded from this. This means that the parties do not consider the issue important enough. Thus, the treaty sets requirements for sustainability, but offers hardly any guarantees or sanctions.

You also say that there is no such thing as sustainable palm oil at all. What do you mean by that?

Indonesia has cleared a lot of rainforest in recent years to promote the export of this product. Even if palm oil is certified organic, this is at the expense of nature. Moreover, the palm oil is transported halfway around the globe – that is anything but sustainable. Last but not least, we can meet our demand with domestic vegetable oils, for example from rapeseed and sunflowers, and with olive oil from Europe.

Isn’t the article on sustainability a first step towards a more environmentally friendly trade?

Indonesia should produce more sustainably, but not export huge amounts of palm oil all over the world. When it comes to sustainability, you have to look at the big picture. Global food production today covers almost all its oil needs with palm oil. This is purely for financial reasons, as it costs almost nothing compared to alternatives. This is the main problem with free trade: it does not manage the resources, but only the wallet.

The agreement with Indonesia also allows Swiss companies to export their products. Don’t you want to support the Swiss economy?

I do not support an economy that destroys. Free trade puts all states in competition with each other, so it is a race for advantages. When trade barriers exist, products and services are chosen on the basis of their quality, not just their price.

But I fully understand that the export industry and domestic production are struggling because they are under pressure from world market prices. That is not sustainable either.

I defend the economy, but only one that has margins and demands guarantees from companies for environmental protection and jobs. But today we are far from that. Local businesses are struggling, while big corporations are taking over everything. We are increasingly losing control.

Many environmental organisations like Public Eye or Greenpeace do not support you. How do you explain that?

As far as I know, they do not support the approach for purely political reasons. The WWF, for example, is a partner of certification bodies and also has local branches in the region. So there are dependencies there. Unfortunately, the associations are content with an agreement that cannot guarantee sustainability. They have not understood that the principle of free trade and its policy of destruction must be fundamentally questioned. •

Souce: swissinfo.ch of 26 January 2021. The interview was conducted by Monika Vuilleumier;

https://www.swissinfo.ch/ger/abstimmung-7--maerz_-der-freihandel-ist-schaedlich-fuer-unseren-planeten-/46315774

(Translation Current Concerns)